Immortal Mullah Nasruddin wins 2nd national storytelling book award

It’s an award!

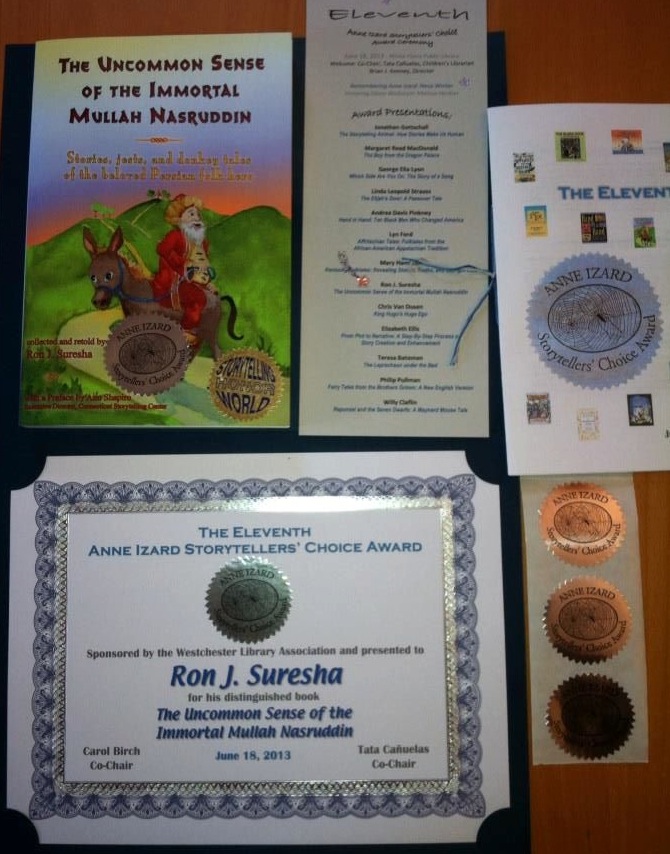

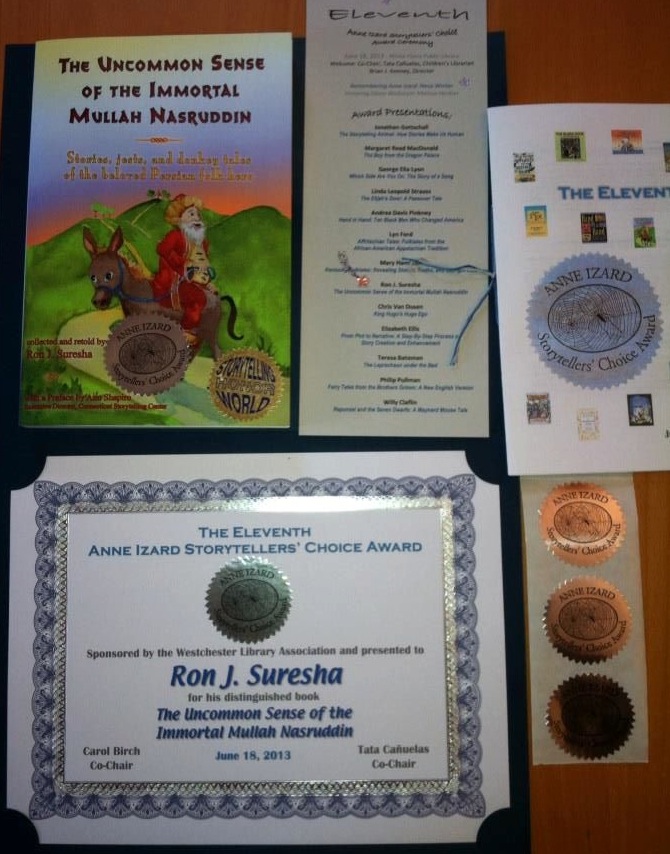

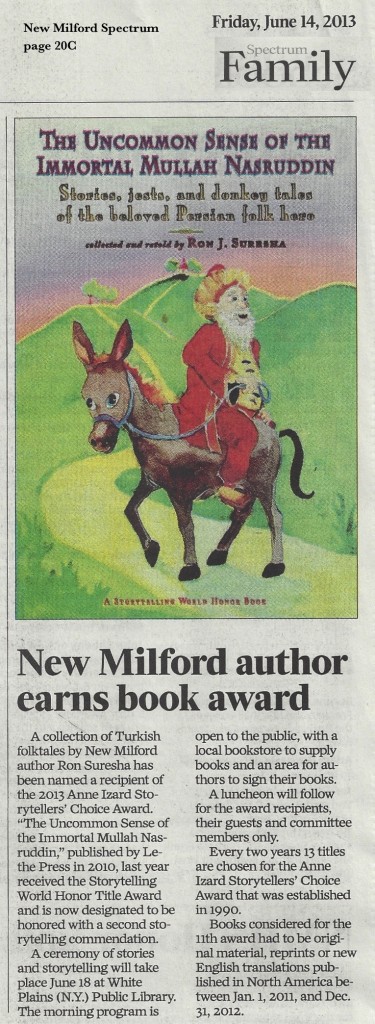

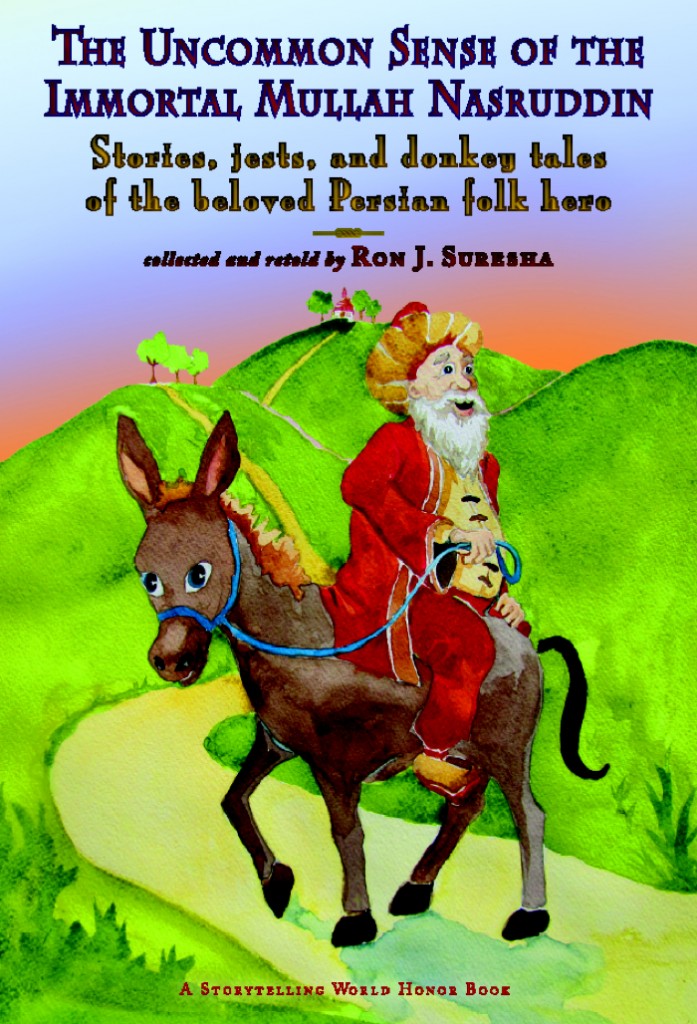

Mullah be praised! The Lethe Press book, “The Uncommon Sense of the Immortal Mullah Nasruddin,” was one of 13 distinguished titles to receive the 11th annual Anne Izard Storytellers’ Choice Award. Three cheers for Steve Berman, who took a chance on a book that was way outside his publishing program.

Here’s the description of the book from the awards ceremony program:

Wise fools are favorites of storytellers and story listeners alike … and no wonder! They allow us to laugh and learn at the same time. Ron J. Suresha collected several hundred stories of the Persian folk hero Nasruddin, from short jokes and anecdotes to longer, fully-fledged tales. He presents them gathered traditionally in groups of seven — seven parts with seven sections each containing seven stories. Well-researched and well-written, this collection is a delight for listeners and tellers alike.

Anne Izard Storytellers’ Choice Awards 2013 recipients:

Recipients of the 2013 Anne Izard Storytellers’ Choice Awards after the awards presentation.

Text of Ron J. Suresha’s presentation at the Anne Izard Storytellers’ Choice Awards:

Anne Izard Storytellers’ Choice Award

Thanks to everyone present, Awards co-chair Carol Birch, White Plains Public Library, and judges of the Anne Izard Storytellers’ Choice Award.

May I take a moment to acknowledge my publisher, Steve Berman, of Lethe Press, who took a chance on this book, which was very outside their publishing program, even after several major Eastern wisdom and storytelling publishers turned it down. I also want to acknowledge my husband, Rocco, who has supported me in every way during my efforts but could not be here today; Ann Shapiro, Executive Director, Connecticut Storytelling Center and everyone at CSC who has offered their amazing resources; and my friend David Juhren, Executive Director of the Loft LGBT Center in White Plains, who’s here today.

That my book, The Uncommon Sense of the Immortal Mullah Nasruddin, is now honored with the Anne Izard Storytellers’ Choice Award, is a tribute for which I am deeply grateful.

Early on, I became well acquainted with the likes of the famous wise fool Mullah Nasruddin, a jokester character of renowned humor and inscrutable wisdom from halfway around the world in the Near and Middle East (also known as Nasreddin Hoca, Djuha, Abu Nuwas, and by other names).

As a child I listened to my mother, an Israeli American who spoke conversational Arabic, recount a few of the droll follies and foibles of the bald, bewhiskered, bumbling Mullah. Threads of his countless fables, anecdotes, and parables, based in Turkish and Persian folk wisdom, were woven into the first stories and jokes that I learned. “You’re acting just like Nasruddin,” my mom would exclaim, exasperated by my contrariness.

Nasruddin was acting up in class one day and insulted his teacher. His teacher Halil berated him, saying, “Nasruddin. How dare you address me this way! Why do you always answer a question with another question‽”

Said Nasruddin, with a smile, “Do I‽”

Sometime after college, I became involved in a yoga community and lived at several ashrams (residential yoga centers) primarily around the United States, as well as two stays at an Indian ashram, where I learned many more Nasruddin tales. These droll stories were included in daily formal lectures by our teachers to illuminate, often with comedic effect, the uncommon foolishness and occasional common sense of human nature.

In 1997, while working as production editor at Shambhala Publications in Boston, I presented a formal proposal for a pocket edition of Nasruddin stories culled from the hundreds of stories in the Shah volumes, but Octagon Press declined the query. From that initial proposal I developed this project, my own contemporary retelling of the Nasruddin corpus.

Over the past 20 years, I have collected and indexed several thousand versions of more than one thousand stories and parables, anecdotes and aphorisms, and jests and jokes of my longtime teacher and friend, Mullah Nasruddin, in his many incarnations in various cultures around the globe. My retellings are based on personal recollection of oral narratives as well as dozens of published sources in English, Spanish, German, French, Turkish, and Hebrew.

Excluding a few longer narratives that incorporate shorter bits, the stories in the book are presented seven at a sitting, as per the oral tradition of Nasruddin’s “curse.”

Once, when the boy was being particularly bad in class, his teacher Halil said:

Wherever you go or stay,

whatever you do or say,

whether it be night or day —

people will only laugh and laugh at you.

Gathered into seven parts having seven sections, each section containing seven stories (73 = 343), the selections comprise the most popular, amusing, meaningful, and compelling ones repeated among my sources. My goals have been to craft fresh, strong, clear presentations of the folklore, to incorporate the best aspects of each known variation, and to adapt the narrative material to contemporary readership.

The stories are arranged into a rough biography, starting with Nasruddin’s childhood and moving through characteristic life passages: his youth and schooling, his married and family life, travels and travails with his devoted grey donkey, the daily labor of his many vocations, encounters with his village neighbors and teahouse chums, his exploits as a favorite in Sultan Tamerlane’s court, his duties and acts as local magistrate and religious teacher, and his old age and death. One of my favorite stories goes like this:

In the little Turkish town of Akshehir where he lived, the immortal folk hero Mullah Nasruddin was a tribal elder and mullah, or learned minister, of his town. As such, every Friday Nasruddin was expected to give the sermon before the true believers, to expound upon the mystic life and other religious matters of import.

Usually he was prepared with a topic, but one Friday morning, however, even as he walked up the stairs to assume his position addressing the congregation, nothing came to mind.

The first time this happened, Nasruddin tried to buy some time. He called forth in a loud, confident voice, “Oh true believers, mark my words, for I am a prophet and the son of a prophet.”

The worshipers sat staring at Nasruddin in slack-jawed disbelief at this apparent infidel.

Someone said, “Nasruddin, if you are the son of a prophet, tell us: what am I thinking right now?”

“I know precisely what you’re thinking right now.” Nasruddin stroked his long grey beard, rubbed his temples with his index fingers, then he cleared his throat. “I can tell . . . that you are thinking . . . that I am a false prophet.”

Then, as he stood before the assembly, an idea flashed in Nasruddin’s brain. Assuming a fierce stance, Nasruddin announced in a strong and severe voice, “O true believers! Do you know the topic about which I have come to speak to you‽”

Puzzled glances were exchanged, and then the people answered in a hushed yet yearning whisper, “No, we don’t understand, not at all, we haven’t a clue.”

Nasruddin looked disparagingly at the congregation. “If you have zero idea of the value of the message you are about to receive, then what is the worth of anything that I could tell you?” And with that, he dismounted the pulpit and exited the mosque, free for the time being. That week, Nasruddin’s cryptic sermon was the talk of the village.

That Friday, again Nasruddin found himself about to address the expectant flock with nothing to say. Taking the pulpit, he announced in an even more fiery tone, “O true believers! I have come here today, to speak to you about a most significant and dire matter. Do you have any knowledge of the subject which I am addressing?”

This time, the group, as one person, rose and responded, “Yes, we do know.”

Nasruddin replied, “Oh, so now you all think you know everything that needs to be understood about the subject, do you? If it’s so obvious, then why should I waste my breath explaining to you what apparently is so apparent?” And he stepped lightly down the seven steps from the pulpit.

All that week everyone in town was abuzz with this latest development. Every man, woman, child, and donkey in Aksehir was debating the matter, and as the week stretched toward the Sabbath sermon once again, the anticipation swelled to immense proportions.

When Friday came around, as it inevitably does, once again Nasruddin found himself without a subject for his sermon. He slowly ascended the pulpit, then proclaimed in a furious roar that made every person in the mosque tremble with the fear of God, “O true believers! Do you know the topic about which I have come to speak to you today?”

As the group had agreed beforehand, half stood up and said, “Yes, we know,” while the other half remained seated and said, “No, we don’t.”

Every head in the room leaned forward to hear the next utterance of the inscrutable Mullah Nasruddin.

“The people assembled here who do understand the matter — and you know who you are! — should teach those who don’t get it.”

And with that, he climbed down the pulpit and looking neither left nor right, neither up nor down, neither outward nor outward, stepped out of the mosque, free and clear — until the next Friday, at least.

This Nasruddin folk tale is sometimes referred to as the story of the learned and the ignorant. This story seems particularly appropriate for this event, as I consider librarians and booksellers and storytellers and editors and writers the learned who are compelled to share their knowledge with the community for others’ benefit.

Many of the numerous anecdotes attributed to Nasruddin reveal a sly, humorous personality with a sharp tongue that spared no one, not even the most tyrannical sultan of his time. The Mullah’s interactions with the despot Tamerlane particularly display an intuitive intelligence shrewd enough to outwit anyone. Thus Nasruddin became the symbol of Middle-Eastern satirical comedy and the rebellious feelings of people against the dynasties that once ruled that area of the world. Here’s a story that embodies that feeling of rebellion, as well as appeals to my sensibilities as an editor.

During Tamerlane’s reign, citizens were banned from carrying any sort of weapon or knife.

One day Luqman, the town constable, stopped Nasruddin on the street and searched him because he thought the Mullah was acting “suspiciously.” Hidden under his turban was a big curved knife.

Luqman shouted at Nasruddin, “Fool, don’t you know that the sultan has forbidden the use of knives‽”

“But I use that to scrape off mistakes and make corrections in the books I read,” Nasruddin protested. In those days, small penknives were used to correct errors in books.

“Is that so‽” said the captain. “Well then, why do you need such a big knife?”

“Because they are large books and there are lots of huge mistakes. Sometimes the errors are so egregious that even this enormous knife isn’t big enough to handle them.”

It is true that by opening the listener’s heart with laughter, the tales create a space for both joy and mystic wisdom to enter. The topper of his teacher’s “curse” imposes the condition that at least seven Nasruddin tales must be told aloud at one sitting. This is done to allow the listener enough time to relax and perceive the humor even in the most pressing situation. Thus paradox, unexpectedness, and unconventional wisdom are fully expressed in the irrepressible good humor and inspirational humanity of the immortal Mullah Nasruddin.

I am currently completing a sequel to Mullah Nasruddin, which will include all the PG-13 material I didn’t include in this volume in order to keep the text reading level at a general college adult readership. It’s an ambitious project, and so I’d like to leave you with one last story about longing and ambition, and one that happens to be appropriate for Father’s Day.

Nasruddin’s father was the head of a large dargah, the burial shrine of a great being, where many seekers, dervishes, and pilgrims would go to worship. Nasruddin used to listen to the pilgrims’ tales of their search for God, and it inspired him to strike out on his own in search of the Truth. His father, Yousef, begged him to stay and help him take care of the temple, but Nasruddin insisted that he had to find his own way to God. Finally Yousef relented, and gave him a little grey donkey to ride as a sort of blessing.

For years Nasruddin wandered from forest to forest, shrine to shrine, and mosque to mosque, until one day at a remote crossroads, his devoted little grey donkey collapsed and died. Nasruddin was inconsolable in the loss of his dear companion. He rolled on the ground, rent his garment, beat his chest, tore out what little hair was left on his balding head, and wailed, “Vai! Vai! My faithful friend and constant companion has died and left me forever!”

As Nasruddin lay there weeping in the dirt at the crossroads, some pious people traveling on pilgrimage saw him in his grief. They took pity upon him and placed leaves and branches over the dead little grey donkey. Others covered it with mud. Someone brought a wooden box to protect the mound from the weather.

Nasruddin just sat there, brooding and silent, staring at the box.

Some charitable folks who lived in a small village nearby passed by the site and, thinking that Nasruddin was the bereaved devotee worshipping at the tomb of a great saint, painted the coffin white out of respect for the Master and his disciple.

Soon the burial site became a regular place of prayer for certain religious persons in the region, who often left heartfelt offerings of flowers, fruit, and incense. One local devotee passed his fez around and collected enough to enclose the box in a marble sarcophagus. Then another eager follower of the anonymous great being within the tomb built an altar before the tomb, and others enclosed the tomb and altar inside a temple, and before long many other true believers began to worship at the shrine of the unknown saint. The local priests were attracted to the new memorial, and of course, soon enough the incense vendors, fruit sellers, and florists heard of the place and set up businesses nearby to sell offerings to hundreds of seekers, dervishes, and pilgrims who came to worship.

Nasruddin by now was very busy running the shrine and had forgotten his sorrow. News spread far and wide that if a person prayed devoutly at the site, his or her prayers would be answered. The shrine drew larger and larger crowds of worshipers, who were all to glad to offer contributions, and from these funds a huge mosque was built. Soon the mosque became quite wealthy and famous, and several hundred people lived in the town that sprang up around it.

Eventually the news of the dargah reached Nasruddin’s village. When his pious father heard of it, he went on pilgrimage to see the great mosque. When Yousef arrived and beheld that it was indeed his own son as the famous mullah of the new holy land, he was overjoyed. He embraced his long-lost child and said, “I’m so pleased at your success, considering the family of failures you’re descended from. But tell me, my son, I am most curious to know — who is the great being buried here in this tomb?”

“O my unjustly proud father, what can I tell you‽” Nasruddin wept into Yousef’s arms. “The truth is: this is the dargah of the little grey donkey you gave me!”

“How peculiar and wonderful,” said Yousef, embracing his son, “that is exactly how it happened in my life. My shrine is that of a donkey that my father gave to me!”

~ ~ ~

My website is ronsuresha.com and the site for the book is mullahnasruddin.com.

Thanks very much for coming and listening so beautifully, and thank you for this award.

You on the Inside, Me on the Outside

You on the Inside, Me on the Outside

Excerpted from The Uncommon Sense of the Immortal Mullah Nasruddin: Stories, Jests, and Donkey Tales of the Beloved Persian Folk Hero

Fatima gave her gold bracelet to the yoghurt-seller in order to cheat him out of an ounce more yoghurt? What sort of bargain is that?

And Nasruddin heartily approves!