A Mullah Nasruddin / Nasreddin Hoca story

Lord, leave me alone

Nasruddin’s mother, Leyla, thought her young son was basically a lost cause. She didn’t know what to do with him, so as a last resort she hired him as an errand boy to an innkeeper. The innkeeper instructed him, “Okay kid, go to the shore and wash out this old wineskin. But do it properly; otherwise, you will be punished!” So Nasruddin took the wineskin to the sea.

And there he washed the wineskin, for all his worth, and continued cleaning it out through the long morning. By the time the sun shone directly above, he wondered, How do I know if it is washed well enough? Who is nearby whose opinion I can ask about this?

There wasn’t a single person on the beach, but offshore there was anchored a fishing ship, with several of its crew on deck. Nasruddin waved the wineskin as a distress signal, and shouted, “Ahoy! Can you help me? Lord, can you bring me there?”

The ship was preparing to pull up anchor and head out to sea when the captain of the ship noticed the boy yelling to him.

“There, on the bank, is a child calling in distress,” the captain said. “We must rescue him! You, sailor, row with a sloop to the shore and fetch the boy.”

Finally, when Nasruddin was brought before him, the Captain asked, “What is the matter, boy?”

“Please tell me, kind sir,” Nasruddin enquired, “in your opinion, is this wineskin well washed?”

Although the captain was just one man, he had the strength of ten men. He put the boy over his knee and spanked him until he was nearly senseless. Weeping in pain, Nasruddin cried out, “What was I supposed to say?”

“You should have instead said: ‘Lord, let them go!’ Now we must regain the time back that we have lost because of you.”

They took Nasruddin back and dumped him in the shallow water, whereupon he threw the wineskin over his shoulder and left the shore. As he made his way across the fields, he chanted his new mantra: “Lord, let them go! Lord, let them run!”

He came upon a hungry hunter who was about to shoot at two rabbits. Nasruddin shouted, “Lord, let them run! Lord, let them go!” The rabbits naturally jumped up and scampered away.

The hunter shouted, “Oh, you bastard! I just missed getting them! You screwed up my hunt!” And he smacked him on the head.

Nasruddin asked, “What should I have said?”

“Obviously, what you should be praying is: ‘Lord, let them be killed!’ or “Lord, let them both die!’ ”

With the wineskin over his shoulder, Nasruddin headed onward, repeating, “Lord, let them be killed. Lord, let them both die.”

And whom did the boy next meet on the road? Two big bearish men in the midst of a heated dispute that had come to blows. Nasruddin fearfully spoke, “Lord, let them kill themselves.”

When the two adversaries heard this, they stopped fighting each other and turned upon him, saying, “You puny punk! Want to stir up some trouble for yourself?” And in cordial harmony they started smacking him around.

When Nasruddin could speak, he cried out, “Please stop — that is not what I meant! But what should I have said?”

“What should you say? You should say: ‘Lord, let them separate!’ ”

“Well, Lord, let them separate! Lord, let them part!” muttered Nasruddin to himself, as he left the men.

Before long Nasruddin passed by a church where a bride and groom who had just been married emerged. As soon as the bride heard the boy intoning the words, “Lord, let them separate!” she made her new husband defend their sacred marriage. The man took off his belt and beat Nasruddin with it as he screamed, “You miserable devil! You want me to be separated from my wife‽”

Nasruddin, who could no longer defend himself, fell to the ground like a dead man. When the bride had raised him again and he opened his eyes, she asked, “Why in the world would you have the lack of sense to say something like that to a new bride and groom?”

Nasruddin replied, “I have no idea why I say anything at all. So tell me, please: what words should I have said?”

“You ought to have said: ‘Lord, let them laugh forever’!”

Nasruddin retrieved his wineskin and went off again, saying the phrase over and again to himself, hoping that he wouldn’t fail again. Then he passed by a house where they were holding a wake for a dead man, with relatives mourning, standing around holding candles. When the dead man’s relatives heard Nasruddin say, “‘Lord, let them laugh forever,” they attacked him. And he received in full what yet he lacked in abuse.

After they finished with him, Nasruddin realized that it was better to keep his mouth shut — though he could barely move his split, bloody lips to speak anyway — and return to the inn.

When the innkeeper saw the boy come in the evening, having sent him early in the morning to wash the wineskin, he demanded, “Tell me, you worthless shithead, where were you all this time?”

But Nasruddin could not utter a single word in his defense. So the innkeeper punished the boy with one more spanking and then sent him home.

Excerpted from

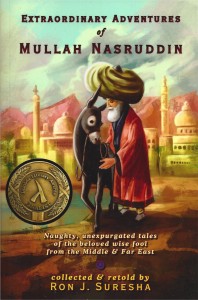

Extraordinary Adventures of Mullah Nasruddin

by Ron J. Suresha

a Lambda Literary Award Finalist

now in print from Lethe Press

~

Order the book from Amazon here.

Order the ebook from Amazon Kindle here.

Order the book from Amazon.uk here.

Order the book from Goodreads here.

The power of chalk

A Mullah Nasruddin / Nasreddin Hoca story

In memory of our fallen heroes: those who threw themselves under the chalklines because someone else was making up the rules of play in the insane asylum.

Excerpted from

by Ron J. Suresha

now in print from Lethe Press

~

Order the book from the Publisher here.

Order the book from Amazon here.

Order the ebook from Amazon Kindle here.

Order the book from Amazon.uk here.

Order the book from Goodreads here.

Order the book from Omnilit here.

Order the book from Smashwords here.