One night as they retired for sleep, Nasruddin stuck his bald head out the window and looked at the stars and sky to assess the weather for the next day.

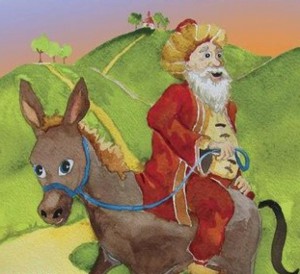

Mullah Nasruddin

“Tomorrow,” he announced to Fatima, who was getting into bed, “if it is pleasant outside, I shall plow the field.”

Fatima glared a warning at him. “God willing! Do not forget to say Insh’allah, my good husband!”

Ignoring his wife’s comment and noting some gathering storm clouds, Nasruddin continued, “If it rains tomorrow, I shall chop wood.”

“Speak carefully, Nasruddin!” rebuked Fatima. “Never, never, never say what you will do without adding Insh’allah! Like this: ‘Tomorrow I shall weave, Insh’allah.’”

Less concerned than she was about this particular religious custom, Nasruddin replied, “Either it will rain or it will shine, and I have decided what to do in either case! If it rains, I chop! If it shines, I plow!” And with that he pulled the covers over himself and was soon snoring soundly.

Fatima knew better than to argue with the sleepy Mullah, but that night her sleep was disturbed by dream after dream of the bad luck that occurs when a good Muslim forgets to say Insh’allah. Nasruddin, however, slept as soundly and loudly as his little grey donkey.

Morning brought a steady chilling rain, but stoically Nasruddin shouldered his axe and headed to the woods. He was hoping that his wife or one of his friends might say a word of discouragement, at which he would gladly have turned around to return home, but alas, Fatima was silent as Nasruddin left, and nobody was out in the awful weather.

By the time Nasruddin trudged along the rutted main road out of the village, he was soaked and cold. Ahead at the crossroads he saw a group of men, one of whom, Nasruddin thought, might be kind enough to dissuade Nasruddin from working in such harsh weather. As he approached them, however, he could see they were soldiers having some sort of argument. He wished he could avoid encountering them, but it was too late — they had noticed Nasruddin approaching.

“Hey, you!” growled the captain of the soldiers at Nasruddin. “Which is the way to Konya?”

Nasruddin tried his best to act stupid. “Don’t ask me! I don’t know,” he shrugged, feigning ignorance. “I am just going to the woods nearby to chop wood,” he said, trying to casually pass by the group of mean-looking soldiers.

This show did not impress the captain, who grabbed the Mullah by his cloak and said, “Oh no, old man, you don’t fool us so easily! We will help you remember!”

The soldiers shook Nasruddin shouted at him and slapped him, until he cried out, “Funny thing! I just remembered the way to Konya now!”

“Then lead us there,” said the captain. “March!”

Drooping his head so dejectedly that his turban seemed to rest on his shoulders, Nasruddin led the group through the rain on the long muddy road to Konya. Presently the mud sucked his shoes off, and then his feet seemed to turn into balls of mud that made it even harder to trudge forward, but any time he slowed, the soldiers brutalized him with curses and fists.

As he plodded on and on, Nasruddin could only think of Fatima, sitting snugly at home, safe and warm, working at her loom . . . wise Fatima, who had common sense and knew enough to have said the night before, “Tomorrow I shall weave, Insh’allah.”

It was nearly dusk when they arrived at Konya, and the soldiers were only too happy to be rid of their guide. Without a word of thanks, they entered an inn and slammed the door shut behind them. Knowing not a soul in the strange town, lacking even two coins to rub together, Nasruddin decided it would be best to use the remaining daylight to try to get home.

Soon enough after Nasruddin began the trek back to Akşehir on this moonless, monsoon-like night, he could see no farther ahead than his outstretched arm. He had to feel his way along the rutted road with his hands to move forward. He was so exhausted that he would have slept in the soft mud, except for his sneezing and coughing impelled him to press on toward home, where Fatima was no doubt warm and dry, having said the proper blessing, Insh’allah.

Well after midnight, Nasruddin stumbled back on the cobblestones of Akşehir. He leaned up against the gate at the entrance to his home and jangled the knocker.

Fatima opened the door to a vision of her exhausted, bedraggled husband, so covered with mud from heels to head that she could hardly recognize him. “Is that you, Nasruddin?” she exclaimed in shock.

“Yes, my wise Fatima,” Nasruddin whimpered, “it is me — Insh’allah!”

One of the most famous Mullah stories. Nasruddin comes to accept Fatima’s superstitious but goodhearted advice, but alas! too late.

One night, Nasruddin’s beloved little grey donkey was stolen. Instead of consoling Nasruddin, the wags in the teahouse the next morning offered only words of remonstration.

Your Daily Nasruddin

Your Daily Nasruddin

Prepare for the Unexpected

Prepare for the Unexpected

“Nobody could climb that tree. It’s way too tall. No way!” yelled Hussein.

“Of course somebody could climb it,” argued Faruk. “Nasruddin, please tell this dunce that this tree is not too tall for someone to climb.”

“I doubt that anyone could climb this tree,” said Hussein, “certainly not even Nasruddin.”

“Of course he can climb it!” retorted Faruk. “He can do nearly anything! Couldn’t you climb it, Nasruddin? I bet if anyone could get up to the top of the tree, it is you.”

Nasruddin bowed slightly and replied modestly, “I can climb it, no doubt.”

“Let’s see you do it, then,” said Faruk.

“I’ll hold your slippers for you while you go up,” said Hussein, perhaps a little too eagerly.

“Well, all right then.” Nasruddin stood back and assessed the tree, and the group of boys, and then the tree again. He rolled up his sleeves, took off his slippers and tucked them into his belt, then spit into his palms as he prepared to scale the tree.

“Wait, wait, Nasruddin!” said Faruk. “You won’t need your shoes in a tree.”

“Yes, leave them here on the ground with us for safekeeping,” chimed in Hussein.

With a gasp and a grunt, Nasruddin heaved himself upward. “You never know — there might be a road at the top of this tree.” he called out as he climbed, “Be prepared, I always say.”

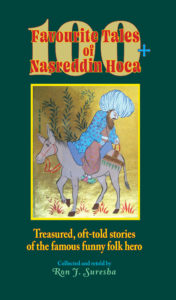

Excerpted from The Uncommon Sense of the Immortal Mullah Nasruddin: Stories, Jests, and Donkey Tales of the Beloved Persian Folk Hero

Another example of how Nasruddin outwits the local boys.

Who knows what might possibly exist at the top of the tree? You certainly won’t know unless you start climbing and keep going until you get there.

There are several other Nasruddin stories in which the Mullah finds himself in a tree, the most popular tale sometimes referred to as Cutting the branch he was sitting on, which ends up after a funeral procession at the graveyard.

Another Nasruddin story that involves climbing a tree was omitted from TUSOTIMN because it portrayed cruelty to a bear. I’ll include it in “Naughty Nasruddin.”